قال تعالى

( وَاذْكُرْ أَخَا عَادٍ إِذْ أَنْذَرَ قَوْمَهُ بِالْأَحْقَافِ وَقَدْ خَلَتِ النُّذُرُ مِنْ بَيْنِ يَدَيْهِ وَمِنْ خَلْفِهِ أَلَّا تَعْبُدُوا إِلَّا اللَّهَ إِنِّي أَخَافُ عَلَيْكُمْ عَذَابَ يَوْمٍ عَظِيمٍ) (الاحقاف)

لقد أخبر القرآن الكريم أن قوم عاد بنوا مدينة اسمها ( إرم ) ووصفها القرآن بأنها كانت مدينة عظيمة لا نظير لها في تلك البلاد

قال تعالى

أَلَمْ تَرَ كَيْفَ فَعَلَ رَبُّكَ بِعَادٍ{6} إِرَمَ ذَاتِ الْعِمَادِ {7} الَّتِي لَمْ يُخْلَقْ مِثْلُهَا فِي الْبِلَادِ {8} (سورة الفجر)

وقد ذكر المؤرخون أن عاداً عبدوا أصناماً ثلاثة يقال لأحدها : صداء وللأخر : صمود ، وللثالث : الهباء وذلك نقلاً عن تاريخ الطبري.

ولقد دعا هود قومه إلى عبادة الله تعالى وحده وترك عبادة الأصنام لأن ذلك سبيل العذاب يوم القيامة .

ولكن ماذا كان تأثير هذه الدعوة على قبيلة ( عاد ) ؟

لقد احتقروا هوداً ووصفوه بالسفه والطيش والكذب ، ولكن هوداً نفى هذه الصفات عن نفسه مؤكداً لهم أنه رسول من رب العالمين لا يريد لهم غير النصح كما هو حال جميع الأنبياء عندما يواجهوا العناد من قومهم

أهم النقاط التي تطرق القرآن لذكرها في قصة هود :

1 - قوم هود كانوا يسكنون في الأحقاف وهي الأرض الرملية ولقد حددها المؤرخون بين اليمن وعمان

2- أنه كان لقوم عاد بساتين وأنعام وينابيع قال تعالى وَاتَّقُوا الَّذِي أَمَدَّكُم بِمَا تَعْلَمُونَ {132} أَمَدَّكُم بِأَنْعَامٍ وَبَنِينَ {133}وَجَنَّاتٍ وَعُيُونٍ

3. أن قوم عاد بنوا مدينة عظيمة تسمى إرم ذات قصور شاهقة لها أعمدة ضخمة لا نظير لها في تلك البلاد لذلك قال تعالى ( ألم ترى كيف فعل ربك بعاد إرم ذات العماد، التي لم يخلق مثلها في البلاد).

4. إنهم كانوا يبنون القصور المترفة والصروح الشاهقة (أتبنون بكل ريع ٍ آية تعبثون، وتتخذون مصانع لعلكم تخلدون).

5- لما كذبوا هوداً أرسل عليهم الله تعالى ريحاً شديدة محملة بالأتربة قضت عليهم وغمرت دولتهم بالرمال

فى بداية عام 1990امتلأت الجرائد العالمية الكبرى بتقاريرصحفية تعلن عن: " اكتشاف مدينة عربية خرافية مفقودة " ," اكتشاف مدينة عربية أسطورية " ," أسطورة الرمال (عبار)", والأمر الذي جعل ذلك الاكتشاف مثيراً للاهتمام هو الإشارة إلى تلك المدينة في القرآن الكريم. ومنذ ذلك الحين, فإن العديد من الناس؛ الذين كانوا يعتقدون أن "عاداً" التي روى عنها القرآن الكريم أسطورة وأنه لا يمكن اكتشاف مكانها، لم يستطيعوا إخفاء دهشتهم أمام اكتشاف تلك المدينة التي لم تُذكر إلا على ألسنة البدو قد أثار اهتماماً وفضولاً كبيرين

منذ اللحظة التي بدأت فيها بقايا المدينة في الظهور, كان من الواضح أن تلك المدينة المحطمة تنتمي لقوم "عاد" ولعماد مدينة "إرَم" التي ذُكرت في القرآن الكريم؛ حيث أن الأعمدة الضخمة التي أشار إليها القرآن بوجه خاص كانت من ضمن الأبنية التي كشفت عنها

قال د. زارينزوهو أحد أعضاء فريق البحث و قائد عملية الحفر, إنه بما أن الأعمدة الضخمة تُعد من العلامات المميزة لمدينة "عُبار", وحيث أن مدينة "إرَم" وُصفت في القرآن بأنها ذات العماد أي الأعمدة الضخمة, فإن ذلك يعد خير دليل على أن المدينة التي اكتُشفت هي مدينة "إرَم" التي

ذكرت في القرآن الكريم

قال تعالى في سورة الفجر :

" أَلَمْ تَرَ كَيْفَ فَعَلَ رَبُّكَ بِعَادْ (6) إِرَمَ ذَاتِ العِمَادْ (7) الَّتِى لَمْ يُخْلَقْ مِثْلُهَا فِى البِلادْ(8)"

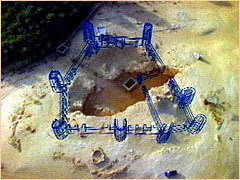

المدينة الأسطورية والتي ذكرت في القرآن باسم إرم أنشأت لِكي تَكُونَ فريدةَ جداً حيث تبدو مستديرة ويمر بها رواق معمّد دائري، بينما كُلّ المواقع الأخرى في اليمن حتى الآن كَانتْ التي اكتشفت كانت أبنيتها ذات أعمدة مربعة يُقالُ بأن سكان مدينة أرم بَنوا العديد مِنْ الأعمدةِ التي غطيت بالذهبِ أَو صَنعتْ من الفضةِ وكانت هذه الأعمدةِ رائعة المنظر "

قال تعالى على لسان نبي الله هود:" أتبنون بكل ريع ٍ آية تعبثون، وتتخذون مصانع لعلكم تخلدون، وإذا بطشتم بطشتم جبارين، فأتقوا الله واطيعون. واتقوا الذي أمدكم بما تعلمون، أمدكم بأنعام وبنين وجنات وعيون ، إني أخاف عليكم عذاب يوم عظيم" الشعراء

ولقد كشفت السجلات التاريخية أن هذه المنطقة تعرضت إلى تغيرات مناخية حولتها إلى صحارى، والتي كَانتْ قبل ذلك أراضي خصبة مُنْتِجةَ فقد كانت مساحات واسعة مِنْ المنطقةِ مغطاة بالخضرة كما أُخبر القرآنِ، قبل ألف أربعمائة سنة حينما كان يعيش بها قوم عاد ولقد كَشفَت صور الأقمار الصناعية التي ألتقطها أحد الأقمار الصناعية التابعة لوكالة الفضاء الأمريكية ناسا عام 1990 عن نظامَ واسع مِنْ القنواتِ والسدودِ القديمةِ التي استعملت في الرَيِّ في منطقة قوم عاد والتي يقدر أنها كانت قادرة على توفير المياه إلى 200000 شخصَ

كما تم تصوير مجرى لنهرين جافين قرب مساكن قوم عاد أحد الباحثين الذي أجرى أبحاثه في تلك المنطقة قالَ" لقد كانت المناطق التي حول مدنية مأرب خصبة جداً ويعتقد أن المناطق الممتدة بين مأرب وحضرموت كانت كلها مزروعة

أما سبب اندثار حضارة عاد فقط فسرته أحدي الصحف الفرنسيه* التي ذكرت أن مدينة إرم أو"عُبار" قد تعرضت إلى عاصفة رملية عنيفة أدت إلى غمر المدينة بطبقات من الرمال وصلت سماكتها إلى حوالي 12 متر

وهذا تماماً هو مصداق لقوله تعالى :

(فَأَرْسَلْنَا عَلَيْهِمْ رِيحًا صَرْصَرًا فِي أَيَّامٍ نَّحِسَاتٍ لِّنُذِيقَهُم عَذَابَ الْخِزْيِ فِي الْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا وَلَعَذَابُ الْآخِرَةِ أَخْزَى وَهُمْ لَا يُنصَرُونَ)

* M’Interesse, January 1993

وهذه مواقع أجنبيه محايده توثق للحقائق العلميه في الموضوع

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ubar/zarins/

http://observe.arc.nasa.gov/nasa/exhibits/ubar/ubar_0.html

الموضوع منقول من موقع موسوعه الإعجاز العلمي في القرأن والسنه

تم تنسيق الموضوع بمعرفتى

سيف الكلمة

( وَاذْكُرْ أَخَا عَادٍ إِذْ أَنْذَرَ قَوْمَهُ بِالْأَحْقَافِ وَقَدْ خَلَتِ النُّذُرُ مِنْ بَيْنِ يَدَيْهِ وَمِنْ خَلْفِهِ أَلَّا تَعْبُدُوا إِلَّا اللَّهَ إِنِّي أَخَافُ عَلَيْكُمْ عَذَابَ يَوْمٍ عَظِيمٍ) (الاحقاف)

لقد أخبر القرآن الكريم أن قوم عاد بنوا مدينة اسمها ( إرم ) ووصفها القرآن بأنها كانت مدينة عظيمة لا نظير لها في تلك البلاد

قال تعالى

أَلَمْ تَرَ كَيْفَ فَعَلَ رَبُّكَ بِعَادٍ{6} إِرَمَ ذَاتِ الْعِمَادِ {7} الَّتِي لَمْ يُخْلَقْ مِثْلُهَا فِي الْبِلَادِ {8} (سورة الفجر)

وقد ذكر المؤرخون أن عاداً عبدوا أصناماً ثلاثة يقال لأحدها : صداء وللأخر : صمود ، وللثالث : الهباء وذلك نقلاً عن تاريخ الطبري.

ولقد دعا هود قومه إلى عبادة الله تعالى وحده وترك عبادة الأصنام لأن ذلك سبيل العذاب يوم القيامة .

ولكن ماذا كان تأثير هذه الدعوة على قبيلة ( عاد ) ؟

لقد احتقروا هوداً ووصفوه بالسفه والطيش والكذب ، ولكن هوداً نفى هذه الصفات عن نفسه مؤكداً لهم أنه رسول من رب العالمين لا يريد لهم غير النصح كما هو حال جميع الأنبياء عندما يواجهوا العناد من قومهم

أهم النقاط التي تطرق القرآن لذكرها في قصة هود :

1 - قوم هود كانوا يسكنون في الأحقاف وهي الأرض الرملية ولقد حددها المؤرخون بين اليمن وعمان

2- أنه كان لقوم عاد بساتين وأنعام وينابيع قال تعالى وَاتَّقُوا الَّذِي أَمَدَّكُم بِمَا تَعْلَمُونَ {132} أَمَدَّكُم بِأَنْعَامٍ وَبَنِينَ {133}وَجَنَّاتٍ وَعُيُونٍ

3. أن قوم عاد بنوا مدينة عظيمة تسمى إرم ذات قصور شاهقة لها أعمدة ضخمة لا نظير لها في تلك البلاد لذلك قال تعالى ( ألم ترى كيف فعل ربك بعاد إرم ذات العماد، التي لم يخلق مثلها في البلاد).

4. إنهم كانوا يبنون القصور المترفة والصروح الشاهقة (أتبنون بكل ريع ٍ آية تعبثون، وتتخذون مصانع لعلكم تخلدون).

5- لما كذبوا هوداً أرسل عليهم الله تعالى ريحاً شديدة محملة بالأتربة قضت عليهم وغمرت دولتهم بالرمال

الاكتشافات الأثرية لمدينة إرم

فى بداية عام 1990امتلأت الجرائد العالمية الكبرى بتقاريرصحفية تعلن عن: " اكتشاف مدينة عربية خرافية مفقودة " ," اكتشاف مدينة عربية أسطورية " ," أسطورة الرمال (عبار)", والأمر الذي جعل ذلك الاكتشاف مثيراً للاهتمام هو الإشارة إلى تلك المدينة في القرآن الكريم. ومنذ ذلك الحين, فإن العديد من الناس؛ الذين كانوا يعتقدون أن "عاداً" التي روى عنها القرآن الكريم أسطورة وأنه لا يمكن اكتشاف مكانها، لم يستطيعوا إخفاء دهشتهم أمام اكتشاف تلك المدينة التي لم تُذكر إلا على ألسنة البدو قد أثار اهتماماً وفضولاً كبيرين

منذ اللحظة التي بدأت فيها بقايا المدينة في الظهور, كان من الواضح أن تلك المدينة المحطمة تنتمي لقوم "عاد" ولعماد مدينة "إرَم" التي ذُكرت في القرآن الكريم؛ حيث أن الأعمدة الضخمة التي أشار إليها القرآن بوجه خاص كانت من ضمن الأبنية التي كشفت عنها

قال د. زارينزوهو أحد أعضاء فريق البحث و قائد عملية الحفر, إنه بما أن الأعمدة الضخمة تُعد من العلامات المميزة لمدينة "عُبار", وحيث أن مدينة "إرَم" وُصفت في القرآن بأنها ذات العماد أي الأعمدة الضخمة, فإن ذلك يعد خير دليل على أن المدينة التي اكتُشفت هي مدينة "إرَم" التي

ذكرت في القرآن الكريم

قال تعالى في سورة الفجر :

" أَلَمْ تَرَ كَيْفَ فَعَلَ رَبُّكَ بِعَادْ (6) إِرَمَ ذَاتِ العِمَادْ (7) الَّتِى لَمْ يُخْلَقْ مِثْلُهَا فِى البِلادْ(8)"

المدينة الأسطورية والتي ذكرت في القرآن باسم إرم أنشأت لِكي تَكُونَ فريدةَ جداً حيث تبدو مستديرة ويمر بها رواق معمّد دائري، بينما كُلّ المواقع الأخرى في اليمن حتى الآن كَانتْ التي اكتشفت كانت أبنيتها ذات أعمدة مربعة يُقالُ بأن سكان مدينة أرم بَنوا العديد مِنْ الأعمدةِ التي غطيت بالذهبِ أَو صَنعتْ من الفضةِ وكانت هذه الأعمدةِ رائعة المنظر "

قال تعالى على لسان نبي الله هود:" أتبنون بكل ريع ٍ آية تعبثون، وتتخذون مصانع لعلكم تخلدون، وإذا بطشتم بطشتم جبارين، فأتقوا الله واطيعون. واتقوا الذي أمدكم بما تعلمون، أمدكم بأنعام وبنين وجنات وعيون ، إني أخاف عليكم عذاب يوم عظيم" الشعراء

ولقد كشفت السجلات التاريخية أن هذه المنطقة تعرضت إلى تغيرات مناخية حولتها إلى صحارى، والتي كَانتْ قبل ذلك أراضي خصبة مُنْتِجةَ فقد كانت مساحات واسعة مِنْ المنطقةِ مغطاة بالخضرة كما أُخبر القرآنِ، قبل ألف أربعمائة سنة حينما كان يعيش بها قوم عاد ولقد كَشفَت صور الأقمار الصناعية التي ألتقطها أحد الأقمار الصناعية التابعة لوكالة الفضاء الأمريكية ناسا عام 1990 عن نظامَ واسع مِنْ القنواتِ والسدودِ القديمةِ التي استعملت في الرَيِّ في منطقة قوم عاد والتي يقدر أنها كانت قادرة على توفير المياه إلى 200000 شخصَ

كما تم تصوير مجرى لنهرين جافين قرب مساكن قوم عاد أحد الباحثين الذي أجرى أبحاثه في تلك المنطقة قالَ" لقد كانت المناطق التي حول مدنية مأرب خصبة جداً ويعتقد أن المناطق الممتدة بين مأرب وحضرموت كانت كلها مزروعة

أما سبب اندثار حضارة عاد فقط فسرته أحدي الصحف الفرنسيه* التي ذكرت أن مدينة إرم أو"عُبار" قد تعرضت إلى عاصفة رملية عنيفة أدت إلى غمر المدينة بطبقات من الرمال وصلت سماكتها إلى حوالي 12 متر

وهذا تماماً هو مصداق لقوله تعالى :

(فَأَرْسَلْنَا عَلَيْهِمْ رِيحًا صَرْصَرًا فِي أَيَّامٍ نَّحِسَاتٍ لِّنُذِيقَهُم عَذَابَ الْخِزْيِ فِي الْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا وَلَعَذَابُ الْآخِرَةِ أَخْزَى وَهُمْ لَا يُنصَرُونَ)

* M’Interesse, January 1993

وهذه مواقع أجنبيه محايده توثق للحقائق العلميه في الموضوع

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ubar/zarins/

http://observe.arc.nasa.gov/nasa/exhibits/ubar/ubar_0.html

الموضوع منقول من موقع موسوعه الإعجاز العلمي في القرأن والسنه

تم تنسيق الموضوع بمعرفتى

سيف الكلمة

This type of "seeing" can take place either from the air or the ground. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), dubbed "the red sled" on the Ubar dig, is a radar device that, when dragged over a site, can give a rough picture of any structure that may lie beneath. Geophysical Diffraction Tomography (GDT) accomplishes the same thing with sound waves coming from an 8-gauge shotgun. But perhaps the most spectacular remote sensing tools are those that create images of earth from the sky.

This type of "seeing" can take place either from the air or the ground. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), dubbed "the red sled" on the Ubar dig, is a radar device that, when dragged over a site, can give a rough picture of any structure that may lie beneath. Geophysical Diffraction Tomography (GDT) accomplishes the same thing with sound waves coming from an 8-gauge shotgun. But perhaps the most spectacular remote sensing tools are those that create images of earth from the sky. To solve that problem, scientists designed and launched the first multi-spectral imaging satellite in 1972. Called Landsat-1, the satellite sent back images of an earth no one had ever seen before. Reading visible light, as well as the infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, Landsat revealed a psychedelic world of magenta vegetation, black water and gold forests. It also showed pollution off the coast of New Jersey, unmapped lakes in Iran and additional branches of the San Andreas fault. "Rocks, soils and vegetation look different at these longer wavelengths," explains Bloom. "And because a lot of materials appear more contrasty at longer wavelengths, they're easier to isolate and detect."

To solve that problem, scientists designed and launched the first multi-spectral imaging satellite in 1972. Called Landsat-1, the satellite sent back images of an earth no one had ever seen before. Reading visible light, as well as the infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, Landsat revealed a psychedelic world of magenta vegetation, black water and gold forests. It also showed pollution off the coast of New Jersey, unmapped lakes in Iran and additional branches of the San Andreas fault. "Rocks, soils and vegetation look different at these longer wavelengths," explains Bloom. "And because a lot of materials appear more contrasty at longer wavelengths, they're easier to isolate and detect."

This multi-spectral data, especially when enhanced by computer processing, can detect the slightest variations in the earth's surface -- like the trail leading to the Ubar site. "The surface material of the incense trail basically had fewer rocks, more sand, and more dust than the surrounding desert," explains Ron Bloom. "That, maybe along with a couple thousand years of camel dung, stood out extremely well at the longer wavelengths."

This multi-spectral data, especially when enhanced by computer processing, can detect the slightest variations in the earth's surface -- like the trail leading to the Ubar site. "The surface material of the incense trail basically had fewer rocks, more sand, and more dust than the surrounding desert," explains Ron Bloom. "That, maybe along with a couple thousand years of camel dung, stood out extremely well at the longer wavelengths." The radar's longest wavelengths were able to partially penetrate the dense jungle vegetation and pick up details of the topography hidden below. As a result, researchers were able to identify water reservoirs and moats around the temple complexes that hadn't been visible from the ground. Similarly, recent radar images of the Great Wall of China found an earlier piece of the Wall -- long suspected to have existed, but never located -- buried under dirt and sand.

The radar's longest wavelengths were able to partially penetrate the dense jungle vegetation and pick up details of the topography hidden below. As a result, researchers were able to identify water reservoirs and moats around the temple complexes that hadn't been visible from the ground. Similarly, recent radar images of the Great Wall of China found an earlier piece of the Wall -- long suspected to have existed, but never located -- buried under dirt and sand. NOVA: Have you been back to Shisur since the time of our filming?

NOVA: Have you been back to Shisur since the time of our filming? JZ: Well, there was a tribal group of people, the Iobaritae or the Ubarites, who lived in the area, and the Shisur site is one of probably three or four major centers from that period. It was a key site with regard to the trade that was coming and going along the edge of the great Empty Quarter. And it's one of those major sites with water. So, there was a lost city of Ubar and we did find it!

JZ: Well, there was a tribal group of people, the Iobaritae or the Ubarites, who lived in the area, and the Shisur site is one of probably three or four major centers from that period. It was a key site with regard to the trade that was coming and going along the edge of the great Empty Quarter. And it's one of those major sites with water. So, there was a lost city of Ubar and we did find it! JZ: I think the most interesting artifacts were the "red polish" pottery wares. My previous work had been in northern and central Arabia, so we weren't familiar with this style of pottery. When we first found it, we thought it was kind of Roman-like, but we soon got our bearings and realized that the pottery showed a clear Parthian influence.

JZ: I think the most interesting artifacts were the "red polish" pottery wares. My previous work had been in northern and central Arabia, so we weren't familiar with this style of pottery. When we first found it, we thought it was kind of Roman-like, but we soon got our bearings and realized that the pottery showed a clear Parthian influence. NOVA: Did you find storage vats for the frankincense at Shisur?

NOVA: Did you find storage vats for the frankincense at Shisur? JZ: Thick walls and towers are generally put in place because of a hostile environment. We know from present day activity that any permanent source of water is always under threat in the desert. Plus they would have had money in there, because they were conducting trade in frankincense and what have you. And so there was always a temptation to rob people.

JZ: Thick walls and towers are generally put in place because of a hostile environment. We know from present day activity that any permanent source of water is always under threat in the desert. Plus they would have had money in there, because they were conducting trade in frankincense and what have you. And so there was always a temptation to rob people.  JZ: Well, the site had just almost completely disappeared under dirt and rock and sand. So, for years, people used to say well there's nothing there but a little tiny observation post that was put in there about 200 years ago. People wrote it off and said there's nothing there.

JZ: Well, the site had just almost completely disappeared under dirt and rock and sand. So, for years, people used to say well there's nothing there but a little tiny observation post that was put in there about 200 years ago. People wrote it off and said there's nothing there. JZ: The most wonderful aspect of this is how remote it is from civilization. It's way out there in the desert. And there are beautiful sunsets. There are huge sand dunes and the Empty Quarter isn't far away and the Bedouin are very friendly. They were very hospitable and we'd get to sit around and drink a lot of coffee. It's a very romantic type of atmosphere. At night you can see all the stars. People used to bring telescopes. You could see the moons of Jupiter with binoculars -- it was so clear. And when they'd turn the generator off, it was total silence. No one had ever experienced that kind of silence before. No cars, no people, no television, no electricity, no airplanes going overhead -- none of that.

JZ: The most wonderful aspect of this is how remote it is from civilization. It's way out there in the desert. And there are beautiful sunsets. There are huge sand dunes and the Empty Quarter isn't far away and the Bedouin are very friendly. They were very hospitable and we'd get to sit around and drink a lot of coffee. It's a very romantic type of atmosphere. At night you can see all the stars. People used to bring telescopes. You could see the moons of Jupiter with binoculars -- it was so clear. And when they'd turn the generator off, it was total silence. No one had ever experienced that kind of silence before. No cars, no people, no television, no electricity, no airplanes going overhead -- none of that. JZ: Well, at first they were kind of suspicious. They didn't know what the heck archaeology was. But we got several people really interested and they actually started finding sites for us. Once they knew what we were after -- we would train them -- they would go out there and find sites for us. They became really interested.

JZ: Well, at first they were kind of suspicious. They didn't know what the heck archaeology was. But we got several people really interested and they actually started finding sites for us. Once they knew what we were after -- we would train them -- they would go out there and find sites for us. They became really interested.

تعليق